Discussion post I submitted for my Atlantic University TP5020 Course – October 16, 2019

To what extent do you think Wilbur’s model is an accurate paradigm of reality for individuals? For the cosmos, as he claims?

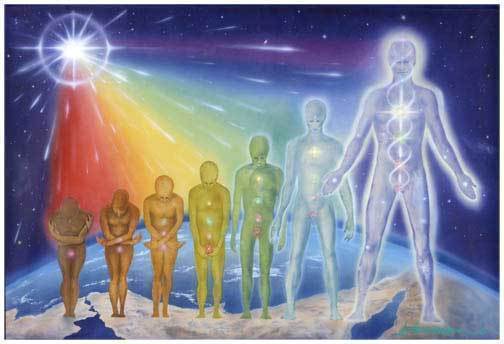

With its roots in psychology, it’s not surprising that there arose a desire to place transpersonal developments into a “neat” and “concise” theory like evolution. If you consider William James was the pioneer of the branch of psychology that would eventually house transpersonal psychology, it’s easy to see how Maslow, Wilbur, and others could apply the notion that things are progressing forward from the simpler to the more complex since everything else since James’ time was displaying similar patterns, and seemingly at the speed of light. Since the turn of the 20th Century, technological advancements have grown exponentially, including major life-changing discoveries like electricity, cars, and mass communications. Medical science and psychology had also progressed in a similar fashion. So why not human systems, the individuals, and the cosmos in general?

There is certainly merit in looking at the progress of human growth and spirituality in this light. But it should not be considered as the end-all to be all. Life, for example, can be looked at in a similar evolutionary fashion. We begin as two cells and after 9-months, we’re born into the world. If we don’t face a terminal disease or an accident, we progress from infants, children, teenagers, young adults, adults, and then finally elderly before we depart the earth plane. Theoretically, we grow in wisdom and experience, which we can pass down to younger generations moving along the same line.

There’s another way to view life, however, and that’s how the movie The Lion King depicts it, which is summed up in its cover song, “The Circle of Life.” Instead of a straight line, this model follows a pattern similar to the 4-seasons. There is a time of birth, growth, aging, and then death just before the cycle starts all over again. I saw this with my own parents. They raised me and provided guidance but as they entered their mid-to-late 80’s, the roles reversed as they essentially regressed in years. I remember being with both toward the end of their respective lives, and it dawned on me how much they were going backward in development. In the end, like toddlers, they slept constantly, required 24/7 care, and even their death can be seen as returning the great unknown similar to a pre-conception period.

What is the danger in favoring hierarchical, evolutionary models of development?

When you consider the complexity of the human mind, the personal nature which spirituality unfolds, and the countless cultures that have developed their own methods of worshiping and creating extraordinary human experiences (EHEs), there is no way it can all neatly fit into a single theory like evolution. Wilbur acknowledges such when he says that every “person’s spiritual path…is radically individual and unique, even though the particular competences themselves might follow a well defined path” (1999, p.7).

Yet, Wilber then goes on to criticize pluralism, where he sees one of its “main activities is not advancing its own constructive conceptions but criticizing and deconstructing everybody goes to great lengths” (1999, p. 117). Respecting and considering a wide range of ideas, current ones and those brought to us by ancient cultures, it’s exactly what’s required when approaching a complex issue like human consciousness and spirituality. As Valle notes, “transpersonal approaches to questions of human psychology and human existence are both ancient and new” (1985, p. 11) People’s beliefs are as diverse and numerous as there have been cultures and humans who have inhabited the earth, and if a theory doesn’t respect divergent’s views, it’s bound to fail.

A genesis of Wilbur criticism of pluralism is rooted in another clear danger of the hierarchical evolutionary approach, and that’s the tendency to look down on the “lower groups” identified in such a model. This type of behavior it’s certainly not limited to academia and to scholars like Wilbur, as it’s seen across a wide swath of life wherever one group believes it has something that others don’t and they are, therefore, “single-out.” Moving away from potentially explosive “labels” and describing groups in terms of “colors” does nothing to mute this ego inflation either. Wilbur squarely positions himself in the “green group,” those “elect” chosen to be on the forefront of the 2nd tier, while the rest of us in the 6 previous 1st tier colors can only hope we’ll be granted admission into the green group someday. While he gives some credit to diverse views of 1st tier colors, his emphasis on the evolutionary process clearly points to his belief that the iPhone 11, for example, while not possible without the iPhone 4, is significantly superior to the latter. I don’t believe spirituality and human consciousness work in the same way, however.

Finally, the quickest way to blow up any theory – particularly in these highly charged and divided times – is to wander into politics. Granted, Wilbur’s article is now twenty years old, but the timeless advice of never discussing politics or religion in mixed company certainly applies here. Having spent more than half my life in national politics, the minute he mentioned the “green group” and their “merits” in relation to “lower tier” colors, I knew exactly where he was headed. And he didn’t disappoint as he spent the latter part of his article emphasizing the need to “integrate Spirit and politics.” Somehow what began as a discussion of his theory on the “evolution of consciousness,” ended up with a political discourse on how to address major issues facing today’s world.

References

Valle, R. (1985). “Transpersonal psychology,” The Humanistic Psychologist, 13-1, pp. 11-15.

Wilbur, K. (1999). “Spirituality and development lines: are there stages?,” The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 31-1, pp. 1-10.

Wilbur, K. (1999). “An approach to integral psychology,” The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 31-2, pp. 109-136.