Discussion Post I submitted for my Atlantic University TP5110 Course – July 30 2020

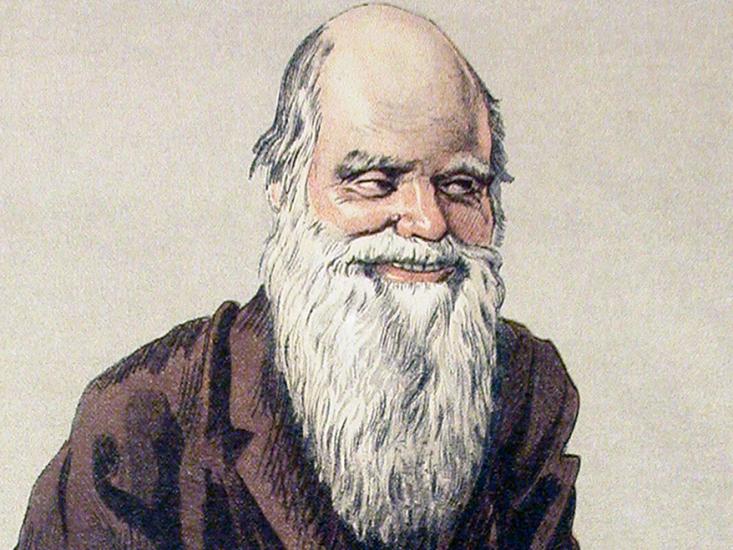

As I mentioned last night, the split between science and religion took a dramatic change for the worse with the widespread acceptance of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution starting at the end of the 1800s. As Peter Harrison notes, despite popular belief that science and religion have been at each other’s throats for centuries, “historians of science have long known that religious factors played a significantly positive role in the emergence and persistence of modern science in the West” (Harrison, 2012).

From the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans, through the early and middle ages of Christianity, and even after the splits that occurred due to the Protestant Reformation and the Age of Enlightenment, science, astrology, astronomy, and philosophy, among others, were pursued within the framework of learning about God’s universe. Religion, Harrison adds, “provided social sanctions for the pursuit of science, ensuring that it would become a permanent and central feature of the culture of the modern West” (Harrison, 2012).

Previous scientific theories altered human’s view that the earth, first of all, was not stationary but in motion, and secondly, it centered around the sun and not the other way around. Darwin’s theory, however, is atheistic at its roots . Taken to its logical conclusions, whether or not he intended it, he paved the way for the belief that we were originated not by an omnipotent Creator but by a random act of chance and ultimately separated from the apes.

As Richard Tanas notes, “Darwin biological evolution was seen as sustained by random variation and defined by natural selection. As the earth had been removed from the center of creation to become another planet, so now was man removed from the center of creation to become another animal” (1991, p. 288). Thus, the split that Robin poses in the question was cemented for more than a hundred years and counting. An unhealthy dichotomy where we must worship at the altar of science for most of our time, except for those rare and safe moments in the privacy of our homes or Sunday mornings, where we can pursue a more integrated mind, body, and soul experience.

The industrial revolution followed shortly after Darwin’s theory burst onto the scene, a logical extension of a mechanical and utilitarian worldview. The exploitation of the workers, particularly women and children, was now made easier since Darwin “proved” that people were not created in the image of likeness of God, and the moral implications that meant, but rather randomly evolved from primordial slime. It is against this backdrop that Pope Pius X issued an encyclical in 1907, Pascendi Dominici Gregis, condemning what he labeled the “heresy of Modernism.” He said that modernism “lay the ax not to the branches and shoots, but to the very root, that is, to the faith and its deepest fibers.” (Pius X, 1907, no. 3)

In retrospect, it’s the emptiness or heresy of modernism at the end of the 20th Century that led me to leave my postmodernist roots and seek answers elsewhere. In 1998, my oldest child was born, and it was a natural time to start questioning the type of environment I wanted to raise him. A cold, cynical, mechanical world wasn’t something I wanted for him or me. I gave a talk recently at the spiritualist church I attend, and when the person introducing me read the part about me converting to Catholicism in 2000, she quipped, “most of us left the Church at that time.” My Dad used to say, “there’s a right way, a wrong way, and Craig’s way,” so I chuckled last night when Lila mentioned she’s been a bit of maverick herself. I believe all of us who find ourselves at A.U. are in one way or another.

While pursuing a Master’s in Catholic theology, I learned how science and religion could peacefully coexist, and that faith could work with reason. We even discussed the whole “Galileo mess” as my professor put it, and like anything taken from history, there is more to the story. They weren’t making excuses, and the backstory is the same as most controversial Church or government decisions since the beginning of time, and that is it was mired in politics. Harrison adds, “It was a difference of opinion on this question that led to Galileo’s confrontation with the Inquisition. Galileo had wanted to insist that the centered Copernican model system was more than a helpful mathematical device – it was an accurate physical description” (Harrison, 2012).

Science, or more accurately, scientism, with its destructive dichotomy that separates humans from God, nature, and themselves, has had a long run, yet their days are numbered. It’s similar to when Copernican approached the Ptolemy issues, not the least of which was his attempt to find a “better calendar” as Tanas says. He adds that Copernican realized that he couldn’t solve the problem by tweaking the old system itself. He “concluded that classical astronomy must contain, or even be based upon, some essential error” (1991, p. 249).

In order to return to a more accurate and holistic view of humanity, I believe it cannot be done by reforming or repairing the relationship between traditional religion and science, or reforming either. Both systems contain “some essential error.” The solution will be something that completely replaces our current worldview. Quantum physics and the merging of Eastern, Western, Indigenous spirituality, transpersonal psychology and a better understanding of consciousness will create an entirely new and expanded way of looking at the Universe, God, and ourselves.

References

Harrison, P. (2012, May 8), “Christiany and the rise of western science,” ABC Religion & Ethics. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/religion/christianity-and-the-rise-of-western-science/10100570

Pope Pius X (1907). Pascendi dominici gregis. [Encyclical letter]. Retrieved from http://www.vatican.va/content/pius-x/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-x_enc_19070908_pascendi-dominici-gregis.html

Tarnas, R. (1991), The passion of the Western mind: understanding the ideas that have shaped our world view, New York: Ballantine Books.

Average of ratings: 100 (1)PermalinkReply