Discussion Post I submitted for my Atlantic University TP5150 Course –July 15, 2020

In her summary of the history of creativity that begins with the cavemen, Nancy Andreasen identifies several aspects that are still relevant today (2005, pp. 1-6). She points out that the modern culture’s view of our prehistoric ancestors as “slumped naked and hair” and “carrying clubs” is likely mistaken (2005, p. 1). She adds that “our ancestors” are “not all that far removed” from us (2005, p. 1) Her observation that these “creative people must have been storytellers” resonated greatly with me (2005, p. 3). Communications, and specifically writing, photography, and videography in the service of telling a story, is what I enjoy the most about my career. Most fundamentally, she identifies that even our prehistoric ancestors had an essential element of creativity, a “spark” she calls it, that allowed them to “see things that did not yet exist” (2005, p. 3).

Andreasen presentation of the role society plays in deciding creativity includes extensive quotes from Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. He believes that for something to be considered creative, it must not only include the individual but specifically the “intersection where individuals, domains, and fields interact” (1999, p 3.) Andreasen, and I, do not ascribe to Csikszentmihalyi’s view that creativity must include domains and fields in addition to the individual. She notes, for example, that unlike Csikszentmihalyi, she thinks that individuals like Vincent Van Gogh, who are not recognized for their creative genius during their lifetimes, “should be defined as exhibiting creativity at the time that they were creating” (2005, p. 15).

In general, I found Csikszentmihalyi’s view limited in that he sees creativity in light of its usefulness and acceptance by the broader culture or society at large. For example, he says that “the ability to convince the field about the virtue of the novelty one has produced is an important aspect of personal creativity” (1999, p. 12). I couldn’t disagree more. I believe the essential aspect of personal creativity is to push the enveloped precisely when the culture is not ready to accept it. And that whether a society ultimately accepts their genius or not has no bearing on whether or not they were creative.

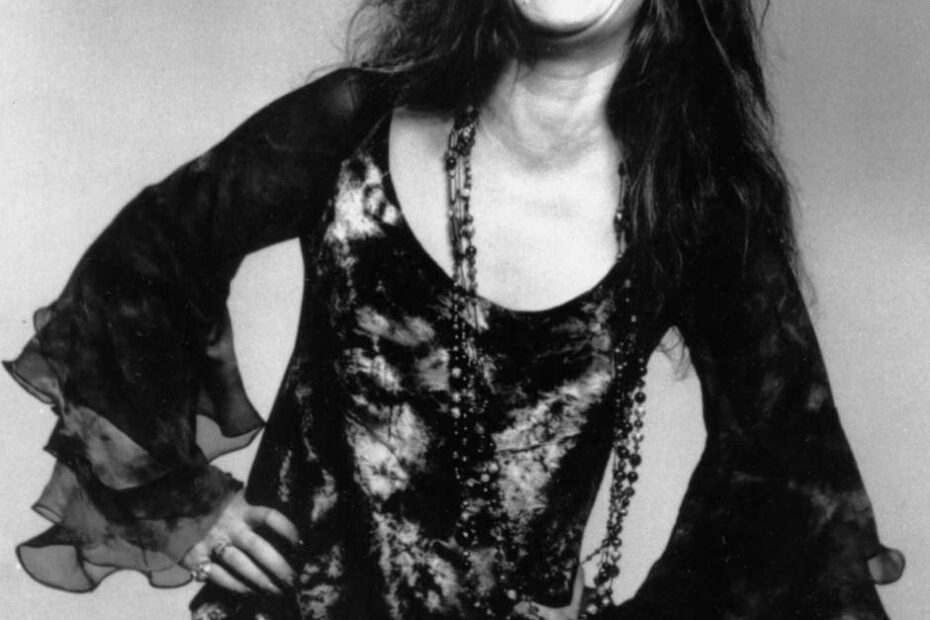

Music in the 1960s comes to mind. Janis Joplin, Bob Dylan, and Neil Young, for example, introduced music never heard before, and fortunately for the rest of us, they helped create a genre still enjoyed today. Unfortunately, by the time the 1970s rolled around, the big record labels demanded specific criteria, like song length and oversight on content in some cases, thereby removing some of the personal creativity of the artists as they were forced into a formulaic approach to selling records. Csikszentmihalyi’s belief that “Creativity cannot be recognized except as it operates within a system of cultural rules” (1999, p. 16) puts him squarely in the camp of the record company executives and not in those of singers and songwriters.

Bunny Paine-Clemes takes creativity in another direction than Csikszentmihalyi. Instead of suggesting that the field and domain are equal partners in creativity, or looking horizontally, she looks heavenward as she presents “Mystical Creativity: ‘The Force’ (2015, p. 35). As she notes, “the mystical view is that some creators feel a higher intelligence is helping and guiding their efforts” (2015, p. 35). She adds volume or a third dimension to Csikszentmihalyi’s limiting view of creativity consisting of domains and fields, along with the individual and describes “Creative Synergy” as a “synergistic reaction between the many and the One, the net, and the gem, the field and the organism” (2015, p.42).

In light of Andreasen’s historical review of creativity, as discussed above, and Paine-Cleme’s addition of other past cultures with similar strains of thought (2015, p. 36), I’d suggest that the mystical view represents an unbroken chain of belief from the beginning of humanity as we know it through today. This belief affirms that creativity includes inspiration from above, a divine source as expressed by many cultures. It’s a paradigm shift in our current time, or at least the mystical view is attempting a comeback after scientism took over the culture starting in the late 1800s. Here’s to it taking hold for good!

Reference

Andreasen, N. (2005), The creative brain: the science of genius, New York, NY: First Plume Publishing

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999), “A systems perspective on creativity,” edited by Sternberg, R. (Ed) (1999), Handbook of creativity,” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 313-35.

Paine-Clemes, B. (2015), Creative synergy: using art, science, and philosophy to self-actualize your life,” Virginia Beach, VA: 4th Dimension Press

Sum of ratings: 100 (1)